Counter Punch

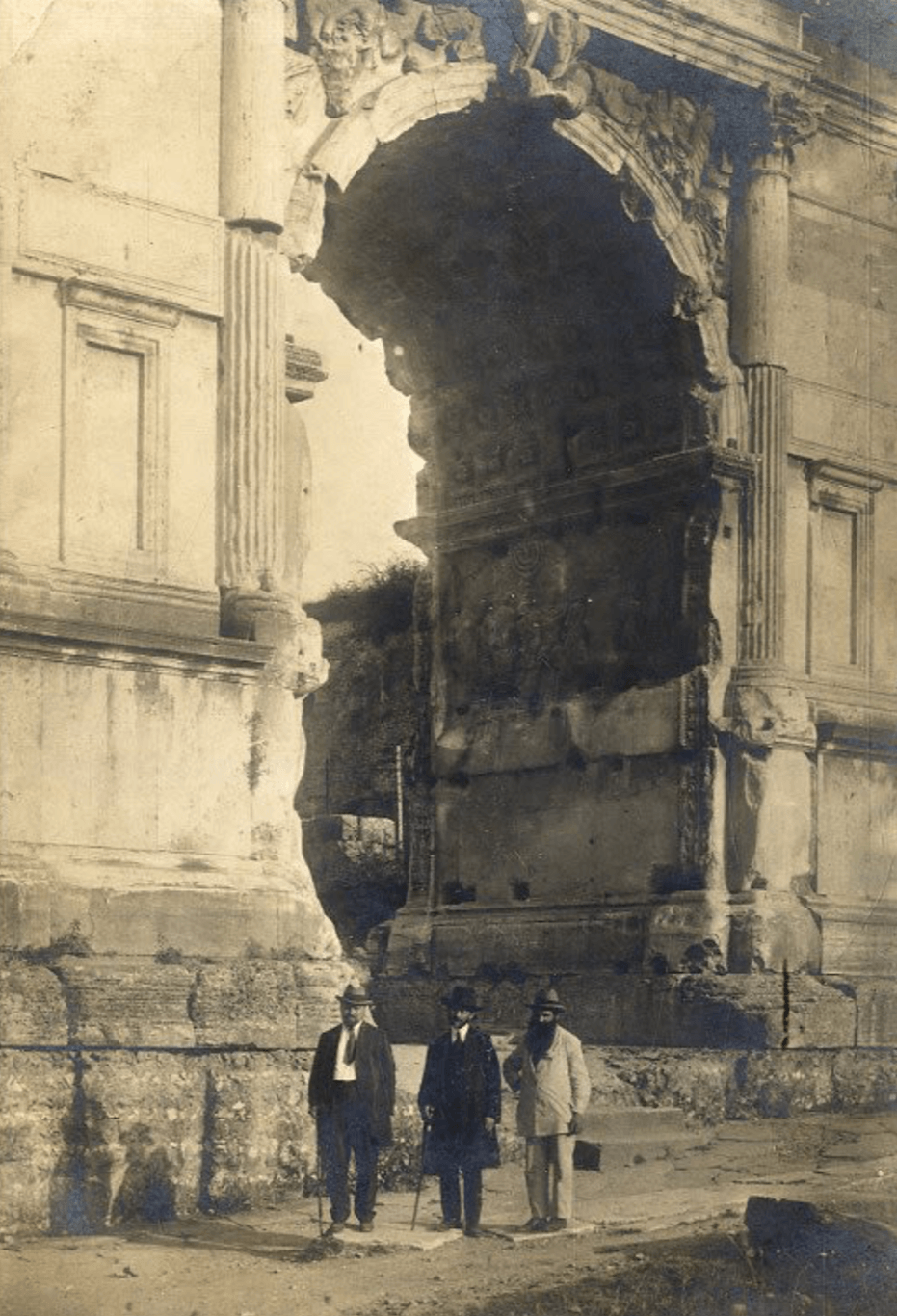

Postcard of Rabbi Yehudah Leib Maimon (middle) between Rabbi Meir Bar-Ilan (left) and Rabbi Shmuel Hayim Landau (right) beside the Arch of Titus, on their way to the Zionist General Council in Rome, 1926.

“To the Victor Goes the Spoils”

The expression dates to 1828, when New York Senator William S. Marcy used it to trumpet the political rewards attending Andrew Jackson’s victory in that year’s presidential election. But the idea that a conqueror may claim the assets of the conquered is of much greater antiquity. In The Iliad, the Greek Diomedes, and the Trojan Hector fought for booty as well as glory. Even Achilles, the greatest of the Greek warriors and a demigod, was a looter. After killing Hector, he took his armor and mutilated his body, vengeance for the killing and desecration of Patroclus, and ostentatious claim for renown (kleos).

The Romans, eager emulators of the Greeks, showed not the slightest trepidation at looting. On the Arch of Titus, erected in 81 CE to celebrate victory over the Jewish kingdom a decade earlier, a sculptural relief shows a procession of Roman soldiers, wearing wreaths of victory, carrying a Menorah and other spoils from the Temple in Jerusalem.

Arch of Titus (South inner panel, showing spoils from the fall of Jerusalem), 81 AD, Rome.

The relief was in Walter Benjamin’s mind when in 1940 he contemplated the tendency of politicians and historians to focus only on the achievements of kings, nobles, the wealthy and powerful. In the seventh thesis of his “On the Concept of History” (also known as “Theses on the Philosophy of History”), he wrote:

“[They] march in the triumphal procession in which today’s rulers tread over those who are sprawled underfoot. The spoils are…known as cultural heritage [which the] historical materialist … cannot contemplate without horror. It owes its existence not only to the toil of the great geniuses who created it, but also to the nameless drudgery of their contemporaries. There has never been a document of culture which is not simultaneously one of barbarism.”

Among the strongest claims of some early Zionism was refusal of this lineage. The Lithuanian Rabbi Aaron Samuel Tamares was exemplary in this respect. Traumatized at an early age by the death of a young neighbor in the Russian-Ottoman War (1877-78), he yearned for a Jewish homeland free of violence. But in the wake of World War I, Tamares renounced political Zionism as a manifestation of the same nationalism and triumphalism that led to the slaughter of millions. He claimed that the essence of Judaism, represented in the Passover Haggadah, was rejection of violence. Tamares wrote: “For the ‘soul is in the blood,’ the Torah says….But this verse will not lie if we interpret it also as reflecting on the soul of the other side.” Jew and gentile are equally worthy of protection. “Never again,” he might have said about genocide a century later, “for anyone, anywhere.”

“Zionism is not in the heavens”

Other prominent Zionists of the period shared Tamares’ anti-nationalism and anti-imperialism, especially the intellectuals of the Brit-Shalom (Covenant of Peace) group of the 1920s and early ‘30s, including the philosopher Martin Buber and the critical theorist and Kabbalist, Gershom Scholem. They believed that the only legitimate state in Mandatory Palestinian was one based on equality of Arabs and Jews. Otherwise, it would fall into the same trap as the imperial states who fought the just concluded war – misrecognizing national ambition as messianic inevitability.

The shift from emancipatory to nationalist, or political Zionism accelerated in the 1920s and ’30s. The passage may be illustrated by an unusual postcard that recently appeared at a Jerusalem auction house. It shows three Mizrachi men (orthodox Zionists from the Middle East) posing beside the Arch of Titus. One of them, Rabbi Yehuda Leib Maimon sent the postcard to his father in Palestine. He wrote in Hebrew, here translated:

“On my journey to the congress of the Zionist General Council on the anniversary of the destruction of our Holy Temple [9th of Av], I went to the Victory Arch of Titus – and I send my greetings to you from there. We won! The People of Israel live!”

The rabbi’s message suggests that the long battle to secure Eretz Yisrael (The Land of Israel) was nearing its end and that the Jews had won. The spoils from the Second Temple looted by Titus and shown on the triumphal arch, would soon be returned — at least figuratively — and Israel redeemed. Maimon went on to become a key figure in Israel’s founding. Twenty-one years after sending his postcard, seated beside David Ben-Gurion at a United Nations Special Committee on Palestine, Maimon told the delegation, mendaciously: “There is an insoluble bond between the People of Israel and its Torah, and there is similarly a strong and enduring tie between our people and this land, the like of which is not to be found elsewhere….From the time of Joshua to the present day, for a period of 3,318 years, Jews have lived in the Land of Israel in an unbroken sequence.”

In fact, many indigenous communities in the world have much longer and deeper ties to a place than Jews have to the land of Israel. Jewish settlement in the region has waxed and waned since biblical times. Just prior to the Jewish-Roman wars of the first and second centuries CE, the Jewish population reached its pre-modern zenith – perhaps a million or more — but the numbers declined precipitously after that. For much of the next two millennia, Jews were a minority in Palestine, rarely more than 15%. By 1880, the Jewish population of the region was about 40 thousand, compared to about 50,000 Christians and 500,000 Muslims. A half-century later, after the establishment of Mandatory Palestine and expanded Jewish immigration, the number of Jews was about 75,00, with about ten times that many Arabs (Muslim and Christian). By comparison, the population of Jews in pre-Holocaust Europe was 9.5 million, with three million in Poland alone. The largest concentration of Jews today is found in New York City – 1.6 million — more than the populations in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv combined.

In November 1947, Rabbi Maimon celebrated the U.N decision to recognize Israel while criticizing its simultaneous recognition of a Palestinian state. Nevertheless, he said, the proclamation marked: “The start of our redemption, the dim twilight of a new morning which is steadily coming towards us.” That posture – of Israel as messianic fulfillment – has dominated Zionist thinking since the nation’s founding and its tragic consequence is now apparent: apartheid and genocide. The latter is defined by the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide as “any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: a) Killing members of the group; b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.” With at least 33,000 Gazans now dead and more than a million displaced, there can be little doubt the UN prohibition has been breached.

The current crisis of Zionism – to deploy genocidal violence or risk being swept away by a popular resistance movement — was foreseen by Scholem in 1929, three years after the Zionist General Council meeting in Rome, attended by Rabbi Maimon and his friends. Though Scholem later endorsed political Zionism, he consistently warned against the tendency to see Israel as the culmination of biblical prophecy. The language he used in an article published in defense of Brit-Shalom anticipates that of his friend, Walter Benjamin a decade later:

“But this victory has now become a handicap and a stumbling block for the entire movement. The force which Zionism joined in those victories was…[that of] the aggressor. Zionism forgot to link up with the…oppressed, which would rise and be revealed soon after. [There were major anti-Zionist protests in Palestine throughout the ‘20s]….Zionism is not in the heavens, and it does not possess the power to unite fire and water. Either it shall be swept away in the waters of imperialism, or else it shall be burned in the revolutionary conflagration of the wakening East.”

Mitvah tantz

Today, the contradiction described by Scholem has been exacerbated by a far-right Israeli government that espouses neo-liberal economics, fundamentalist religion, and autocratic politics. In addition, there are few Israelis today – and none in the ruling coalition – who identify with the victims of imperialism. Socialism in Israel has been all but extirpated, and the behavior of the armies that invaded Gaza exhibit the same, imperial triumphalism that characterized the Roman legions in 70 CE. They appear to revel in killing, looting and destruction; some even see in it an opportunity for mitzvah, the Jewish moral equivalent of the ancient Greek kleos.

Soldiers of the Israeli Defense Forces have marched the length of Gaza carrying with them the spoils of victory: clothes, musical instruments, watches, jewelry, bicycles, mirrors, cosmetics, prayer rugs and even Qur’ans. Looting is widespread and conducted without shame. “There was zero talk about it from the commanders,” one soldier said. “Everyone knows that people are taking things. It’s considered funny — people say: ‘Send me to The Hague.’ It doesn’t happen in secret.” The lack of remorse suggests that the majority of IDF forces share the belief of many Israelis, that the occupation of Gaza combined with expanded settlement in the West Bank marks the long-awaited redemption announced by Rabbi Maimon: complete control of the territory of Palestine from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea.

Death and destruction in Gaza has been accompanied by Israeli dancing. Sometimes soldiers do circle dances amidst the wreckage, like those performed at weddings or bar mitvahs. Sometimes they dance with Torah scrolls, as if it was Simchat Torah, the holiday that celebrates the end of the annual cycle of Torah readings. One video posted online by a soldier shows such a dance in the Medical Faculty Building of the Islamic University, hours before it was blown up. Another reveals a pair of soldiers doing an acrobatic break dance in an area that had been recently bulldozed. Soldiers dance for a variety of reasons beyond simple recreation. They dance to humanize themselves amidst the dehumanized conditions of modern warfare, and to showcase their mastery over their Palestinian enemies. The same triumphalism is manifested by IDF humiliation of Palestinian prisoners, especially men, who are frequently arrested, stripped down to their underwear and transported en mass for detention, interrogation and sometimes torture. Soldiers dance “in triumphal procession…over those who are sprawled underfoot.” In response, the global community must act to indict the perpetrators of the invasion and work to create the state imagined by Brit-Shalom in which Palestinians and Jews have equal claim over land, property, and political power. The Shoah and the brutality of October 7 do not justify the new genocidal outrages, for “the ‘soul is in the blood,” Palestinian and Jew.

No comments:

Post a Comment