The Geopolitics of Water in the Nile River Basin

Global Research, November 15, 2012

Global Research 24 July 2011

In Africa, access to water is one of the most critical aspects of human survival. Today, about one third of the total population lack access to water. Constituting 300 million people and about 313 million people lack proper sanitation. (World Water Council 2006). As result, many riparian countries surrounding the Nile river basin have expressed direct stake in the water resources hitherto seldom expressed in the past. In this paper, I argue that due to the lack of consensus over the use of the Nile basin regarding whether or not “water sharing” or “benefit sharing” has a tendency to escalate the situation in to transboundary conflict involving emerging dominant states such as the tension between Ethiopia-Egypt over the Nile river basin. At the same time, this paper further contributes to the Collier- Hoeffler conflict model in order to analyze the transboundary challenges, and Egypt’s position as the hegemonic power in the horn of Africa contested by Ethiopia. Collier- Hoeffler model is used to predict the occurrence of conflicts as a result of empirical economic variables in African states given the sporadic civil strife in many parts of Africa. In order to simplify my argument and analysis, I focused on Ethiopia and Egypt to explicate the extent of water crisis in the North Eastern part of Africa.

One may question why Ethiopia? My answers are grounded in three main assumptions. The first is based on the failed Anglo-Ethiopia treaty in 1902 which never materialized. The second assumption is based on the exclusion of Ethiopia, since 1902 and the subsequent water agreement of 1929 between Britain and Egypt and the 1959 water agreement between Egypt and Sudan after the later became independent in 1956. The final assumption is the emergence of Ethiopia as a powerful and influential nation in the horn of Africa because of its military power in the sub region.

Ethiopia has pushed forward her demand to develop water resources through hydroelectric power along the Nile. However, for several decades, Egypt has denied other riparian countries complete access to water resources along the Nile, and for that matter has exercised her hegemonic powers over the development and control of the use of water resources in the Nile river basin for many decades. The Nile river basin has survived centuries, and for many years has served as Egypt’s economic hub, political power and growth since ancient times. The water resources in the Nile basins have also served as economic, political, social and cultural achievements of Egypt’s influence in the sub region1.

The water resources in the past were used as trade routes which enhanced Egypt’s mobile communication and international relations for centuries. In which many earlier contacts of Egypt described Egypt as “the gift of the Nile” This hegemonic status enjoyed, since the beginning of earlier civilizations of the ancient kingdoms of Egyptian civilization compelled the ancient philosopher Herodotus to describe this civilization as “Egypt is the Nile and the Nile is Egypt.” This again coincides the period of Egyptian economic boom and its political dominion. What has further entrenched Egypt’s position in the past, which ultimately contributed to Egypt’s power over other riparian countries in the Nile river basin is the 1929 water treaty agreement signed between Egypt and Britain2. Britain, then in charge of many riparian countries as colonies negotiated with Egypt on behalf of its colonies, thereby, giving Egypt an urge over other riparian countries in the use and access to water resources in the river basin.

However, with the attainment of independence by these countries, high population growth, global warming, global economic crisis natural disasters, political development, pollution and resource depletion, industrialization as well as urbanization, high capital cost of water drilling, poor rural electricity for pumping underground water have impelled these riparian countries to engage Egypt’s control in order to re-negotiate earlier water treaties and to abrogate all attempt by Egypt to control the use and development of water resources over the Nile3. Egypt has been in control of the Nile Rivers for a long time and has emerged as the major country that has complete access to the Nile. The shortages of water and water resources in Ethiopia and of course Sudan has prompted those countries to take a second look at Egypt’s access to the Nile, most especially Ethiopia’s attempt to confront Egypt in the Nile river. Berman and Paul concluded that the tension between Egypt and Ethiopia over the Nile is likely to escalate to a war in the future. Due to Ethiopia’s rapidly growing population, in consequence, Ethiopia’s water demand has almost doubled in the last decade4.

Nile River Basin and Declining Water Resources

Nile River Basin and Declining Water Resources

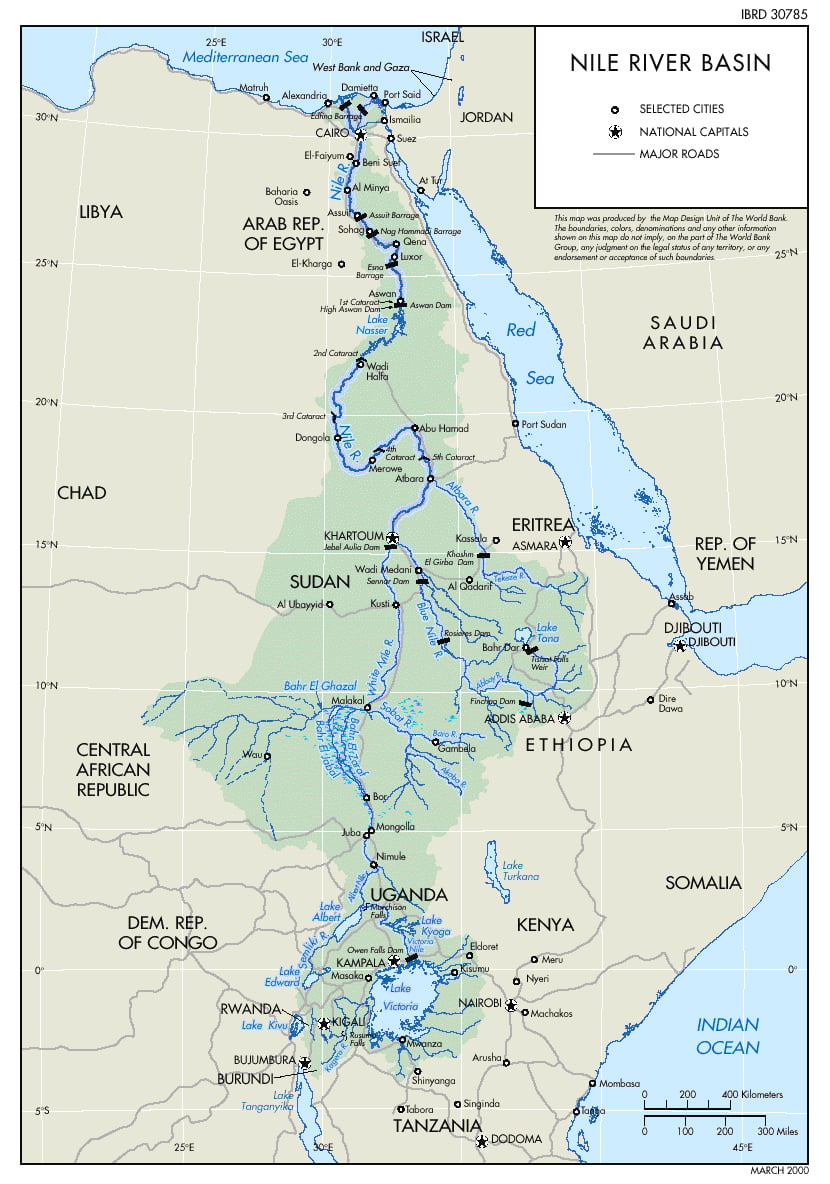

The Nile river basin comprises of ten countries namely, Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda. These countries are known as the ten riparian countries due to their proximity to the Nile river basin5. It is the longest river in the world constituting about 6700 km or 4100 miles long and drains almost all ten aforementioned countries. The flow of the Nile as a naturally endowed commodity has benefited North Eastern countries’ economic activities through agricultural and tourism. About 90% of Egypt’s land mark is desert and therefore, many populations have concentrated along the Nile river basin, due the economic opportunities available along the Nile river basin couple with irrigation activity for landscape farming and animal rearing.6

The complete dependence of water resources over the centuries have caused the Nile river basin to deplete, especially of essential material resources causing high rate of unemployment, diseases and hunger in the countries depending on the water resources. Declan et al, argue that the resource depletion in the Nile river basin is due to three spatial factors, namely global green house effect, regional (through land use) and river basin (land management). This assertion is also consistent with Oxfam studies in Askum region and the drought that has engulfed the entire country. In a brief quote Oxfam indicated the situation in Ethiopia and said:

“Climate variability in Ethiopia is not new – but now, in addition to the usual struggles, Ethiopians living in poverty are additionally suffering the effects of climate change – both more variable climate and more extreme weather events. People who are already poor and marginalized are struggling with the added burden of climate variability. For now, this means that the little that they have goes to dealing with the current unpredictable weather because their livelihoods are so dependent on it. When selling off assets becomes a mean to cope, there is little left to plan for the future. Thus, communities are faced with simultaneously increasing climate variability, and with it increasing risk and vulnerability.7”

Global warming due to climatic conditions and green house emission effect according to Declan et al is one of the contributing factors for the recent water resource decline in the Nile river basin8. They argued that high temperature couple with underground water reduction in the Blue Rivers in Egypt and Sudan is undergoing drastic impact of global warming. As a result, development along the Nile River has led to water resource pollutions by many riparian countries.9

For example, the Ethiopian and Eritrean wars in the late 1990s polluted a substantial part of the river basin with military accoutrements and missile deposits into the Nile Rivers. This pollution activity is further exacerbated by the huge population growth concentrated in the river basin. This populations growth according to the world water council 2006 have double in the last two decades, and continues to rise amidst migrations to the Nile river basins.10

The impact of population pressures and the resource decline in the river basins is also consistent with Aston’s argument that the southern and the northern portions get less rainfall than their equatorial neighboring countries.11 For example the Nile has two confluent tributaries connecting the White Nile and the Blue Nile, the Blue Nile which is considered the most fertile for crop production flows from Lake Tanna in Ethiopia through to Sudan from the South East.12 The Blue and White river basins also coincide with the division of upstream and downstream riparian, and their source of water. While the upstream mainly benefit on water rainfall, the down streams such as the blue river basins enjoys physical flow of water.

Braune, and Youngxin argue that the demand for allocation of water resources has witnessed several treaties and pointed out that “in the past 60 years there have been over 200 international treaties on water and only 37 cases reported on violence between countries.13.” These magnitude of the problem resulted in lack of adequate resolution in resource allocation of water resources.

The impact of Industrialization and mechanization has played a significant role as a result of expansion projects along the Nile river basin. In 2004, the Ethiopian minister for trade accused Egypt of using undiplomatic strategies to control Ethiopia’s development projects on the Nile. Said, “Egypt has been pressuring international financial institutions to desist from assisting Ethiopia in carrying out development projects in the Nile basin.14.”

Farming along the Nile is one of the major sources of livelihood for communities living along the concentrated Nile river basins, but the ensuing drought, famine, population growth and land degradation have impacted the water resources in the Nile river basin. The Environmental Protection Agency in its 2010 report also argued that land degradation and deforestation in the river basin due to excessive burning for land cultivation in many parts of the Nile River has virtually eroded the oasis making it extremely tough for cultivation and water conservation.15

Thus before the 1950s, there were fewer resentments on the Nile water resources by riparian countries, however with changing circumstances such as declining water resources, hunger, and diseases, riparian countries have decided to renegotiate themselves in order to access the Nile. Kenya together with Ethiopia are pioneering this process as seen in the cessionary address to parliament by the Member of Parliament for Kenya Paul Muite in 2004 who remarked “Kenyans are today importing agricultural produce from Egypt as a result of their use of the Nile water.” In a similar statement, Moses Wetangula, the assistant minister for foreign affairs remarked “Kenya will not accept any restriction on use of lake Victoria or the river Nile” and stated “ it however does not wish to be alone ranger in deciding how to use the waters, and has consequently sought the involvement of involved countries.”16

Methodology

Conflict Theory and the Collier-Hoeffler Model

Kofi Anan reiterated that “Unsustainable practices are woven deeply in to the fabric of modern life. Land degradation threatens food security. Forest destruction threatens biodiversity. Water pollution threatens public health, and fierce competition for fresh water may well become a source of conflicts and wars in the future.’’

Kofi Anan reiterated that “Unsustainable practices are woven deeply in to the fabric of modern life. Land degradation threatens food security. Forest destruction threatens biodiversity. Water pollution threatens public health, and fierce competition for fresh water may well become a source of conflicts and wars in the future.’’

This statement by Kofi Anan is buttressed by Amery when he alluded to the Egyptian Member of Parliament’s assertion that Egypt’s “national security should not only be viewed in military terms, but also in terms of wars over waters17.” The horn of Africa has been bedeviled by conflicts, both interstate and civil wars for several years now. These conflicts are mainly concentrated on the north east and central Africa. While many of these conflicts have been disputes over land occupation in mainly oil rich areas of the Congo, others have been the issue of diverting water resources. This paper examines the water scarcity in the North East with an attempt to focus on Egypt and Ethiopia through the Collier-Hoefer model of theory of civil wars in order to construct the model on water scarcity with an attempt to reconcile the tensions over water resources and its effects on the people of the north East African people.

There have been several applications and interpretations of the earlier conflict theorists propounded by earlier scholars such as Karl Marx, Lenin, and Weber. Collier-Hoeffer, also known as the C-H model is one of such interpretation of recent times. Their analyses on conflict is based on the framework of many variables such as tribes, identities, economics, religion and social status in Africa, and subjecting the data to a regression analysis and concluded that of the many variables identified in Africa and the examination of the 78 five year increments(1960-1999) in which conflicts occur, and of five year 1, 600 inputs in which no conflicts occur, concluded that based on the data set that economic factors rather than ethnic, or religious, identities are the bane of conflicts in Africa. In complementing this model with the earlier conflict theory propounded by Karl Marx, Marx, recognized the significance of the social and interactions within a given society. These interactions according Karl Max are characterized by conflicts. Hence, the conflict between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie of the capitalist system forms a synthesis of the forces of the interaction within the system.18

Marx, again reiterated the fact that these social and human interactions is dialectical in the sense that when a dominant nation seeks to control dependent nations or peripheral countries what yields in consequence is the tension to rebel against the oppressor by dependent states in order to agitate for equitable and fair share of national resources. This point is consistent with the C-H model when they argued with empirical data on the causes of conflicts in Africa, and concluded that economic factors are the significant predictor of conflict in many parts of the African continent. Therefore, according to C-H, economic reasons contributed to a large extent the greater portion of conflicts in Africa19. While these economic reasons are varied and numerous due to the resources available in a given region and the allocation of resource whether naturally endowed or man-made, any form of competition to control these resources or allocation of resources will naturally generate two outcomes: tension and potential conflict, and cooperation. In this case, Egypt’s sole access to the Nile for centuries now has invariably gratified itself as the sole control of the Nile water resources.

As a result of the 1929 mandate that gave Egypt absolute control of water resources in the Nile, she has worked to sabotage many riparian countries through other diplomatic and international treaties. Ethiopia has vowed to engage Egypt over the control of water resources in the Nile valley basin. This is exemplified in many water agreement initiated by Ethiopia and the other riparian countries to abrogate all previous agreement hitherto entered by Egypt. Consequently, Stars argues that the looming tension between Egypt and the riparian countries initiated by Ethiopia is a recipe for conflict in the North Eastern Africa20. For instance, these tensions are exemplified in Egypt’s response to Kenya’s assistant foreign affairs minister’s statement when Mohammed Abu Zeid, Egypt’s minister for water resources remarked that Kenya’s statements were a “a declaration of war” against Egypt and subsequently threatened Kenya of economic and political embargo.21

This looming tension among riparian countries is further worsened by Kenya’s continuing threat of engagement. In 2002, a senior Kenyan minister Raila Odinga, called for the review and renegotiation of the 1929 treaty which gave Egypt the right to veto construction projects on the Nile river basin, and said “it was signed on behalf of governments which were not in existence at that time.” This paper’s argument is further rooted in the idea that there are emerging players such as Kenya and Ethiopia in the horn of Africa as major hydro-political powers to engage Egypt’s hydro-hegemonic status. Prior to the Nile basin initiative in February 1999, Wondwosen, argues that there have been several similar water treaties such as the 1993 Technical Committee to promote development cooperation among riparian countries. Also, in 1995 the Nile Basin Action Plan was launched, and in 1997, the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) through collaborations with the World Bank attempted to foster cooperation among riparian countries to promote dialogue.22

This initiative including earlier treaties already mentioned shows the magnitude of the problem in the Nile basin, and of course the consensus necessary to equitably allocate water resources and thereby encourage development projects along the Nile. In 2010, for instance, Ethiopia announced that it was initiating a hydro-electric development projects in order to improve its country’s electric and energy needs. This announcement few days later saw resentment by Egypt and Egypt attempt to veto any such policy along the Nile. While Ethiopia is poised to making this project reality, Egypt has begun galvanizing international support in order to prevent Ethiopia from undertaking such projects.

Cascao, argued that the asymmetrical flow of water resources in the Nile river basin and the access to physical flow of the blue Nile by Egypt and Sudan in the downstream has extremely heighten hydro-political tension over the Nile. These tensions have attracted the United Nations organizations interventions and other international organization on matters concerning the distribution and allocation of water resources in the Nile river basin and in which compensation are offered to other riparian countries unequal access to the distribution of water resources, especially those on the upstream who only benefit rainfall.23

Thus in 1999, nine riparian countries met in Dar Es Salem, Tanzania by the Council of Minister of Water Affairs of Nile River Basin Countries and agreed to cooperate in solidarity for equitable allocation of water resources in the Nile basin as well as for economic integration through sustainable development.24

This economic solidarity through cooperation is declared in the Nile Basin Initiative as the shared vision by riparian countries to promote cooperation and economic well being, while at the same time “to achieve sustainable socio-economic development through the equitable utilization of, & benefit from, the common Nile Basin water resources25.” This Nile Basin Initiative is the first attempt by riparian countries to push demand for equal access to the Nile, and at the time promoting economic cooperation. Egypt’s defiance of the NBI and its lack of participation in the NBI’s initial attempt to convene such a cooperation agreement is a crucial aspect of the NBI’s objective to consolidate through cooperation in the negotiation for equitable distribution. The subsequent institutional mechanism for policy guidelines for riparian countries to agree to follow is set forth by NBI in order to stimulate cooperation rather than intimidation in the allocation of water resources.

The following objectives in February 1999 were set up by the NBI as follows:26

• To develop the Nile Basin water resources in a sustainable and equitable way to ensure

• prosperity, security, and peace for all its peoples

• To ensure efficient water management and the optimal use of the resources

• To ensure cooperation and joint action between the riparian countries, seeking win-win gains

• To target poverty eradication and promote economic integration

• To ensure that the program results in a move from planning to action.

• prosperity, security, and peace for all its peoples

• To ensure efficient water management and the optimal use of the resources

• To ensure cooperation and joint action between the riparian countries, seeking win-win gains

• To target poverty eradication and promote economic integration

• To ensure that the program results in a move from planning to action.

Thus among the NBI’s core functions include among others to promote water resource management, water resource development and capacity building enhanced through cooperation. These initiative have proven worthwhile, in preventing a escalating a major conflict in the region, although there are still tensions among riparian countries along the Nile. Egypt still exercises hydro hegemonic powers in the region because of her absolute control of the Nile basin, Egypt has participated and is willing to cooperate with other riparian countries in bringing lasting solutions to the increasing demand of water resources on the Nile river basin. When it comes down to water resource allocation and distribution, it has always been sidelined and not considered a significant issue in the solution to the Nile problem.

Africa’s interstate conflicts in the past have been on a number of issues such as ethnic and tribal as well as land disputes and acquisitions. The discovery of oil however has proven to be a blessing in disguise in many of the oil regions of Africa. In the Congo for instance, there have been several conflicts with rebels over the control of oil regions of the Brazzaville. This area has not been spared of violence and mayhem for several decades now. In Nigeria for example, the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) has created havoc and tensions culminating in violence and attacks on oil expatriates in the Niger Delta region. These oil regions in Africa today are bedeviled with conflicts, violent attacks and conflicts in order to control oil resources. The least said about the diamond and gold areas of sub Saharan Africa the better. Similarly, and in consistent with the paradigm this paper takes is the assertion that water conflicts like many of the natural endowed assets bestowed on the African continent is a bane for the continent’s development. In the cases of the Nile, although there is no any imminent conflict, scholars are predicting that the lack of concrete and up-to-date resolution on the water policy regarding the distribution of water resources on the Nile is a recipe for conflict in the region.

Relations of Power

As already mentioned and by extension Herodotus comments on Egypt as “the gift of the Nile,” has been extrapolated by Egypt in order to exercise hydro-political power in the Nile river basin for several decades. This status Egypt has enjoyed for some time now without allowing any riparian countries along the Nile to negotiate any form of control on water resources and development projects such as hydro electric power by neighboring countries. The asymmetrical flow of water resources in the Nile has also afforded Egypt a position of dominance compared to other riparian countries who are situated upstream on the Nile. The Nile’s downstream is currently housed by Egypt and Sudan, consequently, Sudan’s attempt to renegotiate Egypt’s unilateral control on the Nile27.

As already mentioned and by extension Herodotus comments on Egypt as “the gift of the Nile,” has been extrapolated by Egypt in order to exercise hydro-political power in the Nile river basin for several decades. This status Egypt has enjoyed for some time now without allowing any riparian countries along the Nile to negotiate any form of control on water resources and development projects such as hydro electric power by neighboring countries. The asymmetrical flow of water resources in the Nile has also afforded Egypt a position of dominance compared to other riparian countries who are situated upstream on the Nile. The Nile’s downstream is currently housed by Egypt and Sudan, consequently, Sudan’s attempt to renegotiate Egypt’s unilateral control on the Nile27.

In 1959, a water agreement signed between Egypt and Sudan gave Egypt 55bcm and 18bcm to Sudan. Again this uneven allocation of resource points to asymmetrical power relations of riparian countries ability to negotiate Egypt to access water resources28. Cascao, provides a theoretical understanding on this hydro power hegemony of Egypt in controlling water resources. And indicated that the hegemonic power of Egypt is due to many factors in the horn of Africa, but argues that this hegemonic status is about to end as counter hydro hegemonic powers are beginning to emerge in order to contest Egypt’s long standing hegemony in the region. I totally agree with Cascoa, and in fact her analysis is in line with my argument that the position Egypt finds herself is about to change due to first the declining rate of water resources in the Nile.

This is because in the past when life was booming riparian countries made no mention of inequity if water resources however, with the emergence global water crisis due to global warming these riparian countries are beginning to contest power relation on the access to the Nile. Cascao points to “apparent consent” to illustrate the apparent lackadaisical attitudes of consent by riparian countries. This apparent consent, Cascoa argues was latent consents by riparian countries along the Nile on many agreements that were signed as far back in 1902. Ethiopia is a case in point. In many of these water treaties Reginald points to about 60 water agreements since the first one in 1902 which either ignored Ethiopia or Ethiopia decided to apparently consent to by keeping mute to the issue. But what is significant is a looming civil war among riparian countries. There have been scuffles between Sudan and Burundi, also Ethiopia and Eritrea and Rwanda and Somalia in the past several decades without totally engaging Egypt’s hydro-hegemonic power in the region, given the emerging hydro political configuration that is beginning to unravel29.

In order to understand the relations of power and dominance in regards to the situation in the Nile river basin it is prudent to again invoke Cascao analysis of power and dominance as they significantly hinges on the Ethiopia’s counter hegemonic strategy in the Nile river basin for some time now. Cascao begins by citing Gramsci’s definition of hegemony as “political power that flows from intellectual and moral leadership, authority, or consensus as distinguished from armed force30” she continues to argue “power is relational and the outcome of hegemonic power relations is determined by the interaction of diverse actors” diverse actors for me seem meaningful and significant here in terms of the power relations here. It can be recalled that there are ten riparian countries each diverse with varied needs and demands in regard to the fair allocation of water resources in the Nile. This diversity is yet galvanized for a common interest as seen in the Nile basin initiative put forth by the nine riparian countries.

Once gain the significant portion Egypt occupies comes under a counter hegemonic truce by riparian countries to renegotiate earlier treaties concerning the Nile river allocation of resource which is consistent with Cascao assertion that “power relations are not static or immutable” and points to a dialectical thesis of challenging the status thereby bringing in new status quo with alternatives. This dialectics is one earlier propounded by Marx and Lenin in their conflict theories regarding the suppression of groups and their simultaneous revolt of the existing status quo. In the case of the river basin, these riparian countries see themselves as having asymmetrical power relations with Egypt, and because Egypt’s consistent dominance in both economic and hegemonic political relations in the sub region, there is an attempt to contest existing status quo as seen in the earlier water treaties and allocation of resources in the Nile basin.

Based on the accusations and counter accusations on the allocation of water resources along the Nile, Ethiopia like Egypt have both galvanized for support in terms of international diplomacy and legitimacy over the use of resources in the Nile. While Egypt continues to maintain its legitimacy based of the earlier water agreements and proclamations that exclusively gave Egypt dominance with right to veto any development projects, Ethiopia has taken its stands to engage Egypt on talks to renegotiate Ethiopia’s position of the Nile resources. When it comes to international funding on the Nile river basin, the IMF and the World Bank has withhold funds for development along the Nile because of the looming tension between the riparian countries and has promised not to get itself tangled on the water crisis along the Nile river basin.31

“Water sharing” or “benefit sharing”

The debate as to whether “water sharing” or “benefit sharing” has dominated many scholarly discourse on the Nile issue. According to Teshome, benefit sharing is “the distribution of benefits through cooperation” and argues furthermore that “benefit sharing gives riparian states the chance to share the benefits derived from the use of water rather than the physical distribution of water itself32.” Teshome’s analysis regarding benefit sharing through cooperation sounds a laudable alternative to riparian countries capacity to cooperate in order to tap water resources, but this argument is idealistic given the power relations along the Nile, and the asymmetrical flow of water resources in the upstream and downstream countries could be difficult to ascertain. I offer the following reason to buttress my argument.

The debate as to whether “water sharing” or “benefit sharing” has dominated many scholarly discourse on the Nile issue. According to Teshome, benefit sharing is “the distribution of benefits through cooperation” and argues furthermore that “benefit sharing gives riparian states the chance to share the benefits derived from the use of water rather than the physical distribution of water itself32.” Teshome’s analysis regarding benefit sharing through cooperation sounds a laudable alternative to riparian countries capacity to cooperate in order to tap water resources, but this argument is idealistic given the power relations along the Nile, and the asymmetrical flow of water resources in the upstream and downstream countries could be difficult to ascertain. I offer the following reason to buttress my argument.

Most significantly, the lack of political will to cooperate by riparian countries is the number one reason benefit sharing could be difficult to achieve. Several water agreement have been launched since the 1929 Anglo Egyptian water agreement that gave Egypt the exclusive power to monitor development activities along the Nile. The lack of political will is clearly demonstrated by Ethiopia’s “apparent consent” to many water treaties that has been passed. The most recent treaty the Nile Basin Cooperative Frame Work Agreement launched in (1997-2007) shows the nature of participation by riparian countries to cooperate to achieving common goals and the allocation of water resources. This lack of political will is also consistent with Teshome argument that the lack of political leadership has exacerbated the situation to the extent that at present there is no international treaty or agreement that binds riparian countries together. Although the many cooperative agreements between upstream and downstream riparian have sidelined issues bordering benefit sharing in their agenda33.

In addition, problem in benefit sharing cooperative agreement is the fact that many riparian countries comes from different political and socio-cultural backgrounds and are therefore prone to series of political and civil upheavals that will endanger any attempt by riparian countries to cooperate for mutual benefit sharing. The most significant one is the Ethiopia Eritrea conflict that has rocked the region for several years, also the Somalia civil conflicts, the Rwanda Burundi and many others in Sudan has worked to prevent many cooperative agreement to realize its potential. Although mutual benefit is essential its implementation to a full potential is unattainable.

This argument is also supported by Cascao when she argued that cooperative agreement can be a “battle ground for opposing tendencies” (p24) Not only that but, also Egypt’s power and international diplomacy over the region. It is indeed important to acknowledge the role of Egypt’s diplomatic relations in the past that has ushered its dominance over the Nile. The strategic position of Egypt on the Suez Canal has been a strategic location for British involvement in Egypt and for British access to India through the canal. This important location of Egypt was advanced by British interest in India34. Benefit sharing or cooperative agreement by upstream and downstream countries have been in opposing terms for quite some time now. The recent National Basin Initiative (NBI) has been used as a platform by Ethiopia to get the 1959 water agreement between Egypt and Sudan annulled, since Ethiopia was excluded, and for that matter the other seven riparian countries in order to enact a comprehensive water policy that will promote the advancement of cooperative water sharing without hostilities.

Also, significant factor that hampers any cooperative agreement on benefit sharing is Egypt’s diplomatic influence on the region. If all riparian countries agree to benefit share these cooperative agreement maybe lopsided and for that matter benefit Egypt more than the other riparian because of Egypt diplomacy with Britain and US, and the international organizations including the Arab league. This point is argued in Teshome when he said “Egypt has been pressuring international institutions to desist from assisting Ethiopia in carrying out development projects in the Nile basin …it has used its influence to persuade the Arab world not to provide Ethiopia with any loans or grants for Nile water development.”

My final alternative is that several water sharing agreements have been adopted by riparian countries at least since the 1959 between Sudan and Egypt in terms of allocation of water resources. This allocation which earmarked 18 BCM to Sudan and 55BCM to Egypt is seen by Sudan as an unfair deal and have since pushed forward for renegotiation on the allocation of water resources that has given Egypt an unfair proportional distribution of resources and for development projects on the Nile. This last alternative could be dangerous in if physical allocation of water resources are to be shared among riparian countries through demarcation, this is because land demarcation and allocation of resources have been one of the dangerous recipe for conflicts currently ongoing on the continent, to physically allocate recourses is nothing but to add more insult to injuries. With emerging hydro-political powers in the region, Ethiopia and Egypt could dominate other countries and for that matter wage physical wars in order to control water resources.

On the basis of the above discussions, it can be safely concluded that the nature of tension in North Eastern Africa most, especially the Nile riparian countries are on a brink of conflict over the control and use of Nile water resources. As already pointed out, and by extension Collier-Hoeffler’s economic analysis of conflicts in Africa did not cite the potential trigger of conflict as a result of the Nile, what is significant about his model is the paradigmatic nature upon which his theory of analysis are based. And since water is a vital part of the economic resources of Africa, this papers concludes that the water resources just as any other economic resource has a full potential of tension and conflict over the Nile river basin by riparian states.

Notes

1.Wonddwossen Teshome B. “Transboundary Water cooperation in Africa: The case of the Nile Basin Initiative.” Turkish Journal of International Relations winter Vol. 7.4 2008 pp34-43

Also see Flintan, F. & Tamarat,I Spilling Blood Over Water? The case of Ethiopia, in Scarcity and Surfeit, The Ecology of Africa’s Conflict. Lind &J.& Sturman K.(eds) Institute for Security Studies, Johannesburg (2002)

2.Ibid

3.Ashton, Peter J. “Avoiding Conflicts over Africa’s Resources” Royal Swedish Academy of Science. Vol.31.3, 2002 pp236-242

4.Berman and Paul, “The New Water Politics of the Middle East. Strategic Review, Summer 1999. 21-28

5.Wonddwossen Teshome B. “Transboundary Water cooperation in Africa: The case of the Nile Basin Initiative.” Turkish Journal of International Relations winter 2008 Vol. 7.4 pp34-43

6.Alcamo, J., Hulme, M., Conway, D., & Krol, M. “Future availability of water in Egypt: The interaction of global, regional and basin scale driving forces in the Nile basin”. AMBIO – A Journal of the Human Environment, 25(5), (1996). 336.

7.Oxfam 2009 report

8.Kim, U., & Kaluarachchi, J. J. “Climate change impacts on water resources in the upper Blue Nile river basin, Ethiopia.” Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 45(6), (2009). 1361-1378.

9. ibid

10.World Water Council Report 2006

11.ibid

12.Wonddwossen Teshome B. “Transboundary Water cooperation in Africa: The case of the Nile Basin Initiative.” Turkish Journal of International Relations winter 2008 Vol. 7.4 pp34-43

14.Braune, Eberhard and Youngxin Xu2. “The role of Ground Water in the Sub Saharan Africa.” Vol. 48.2 March 2010, pp229-238

16.Cam McGrath and Sonny Baraj “Water Wars Loom along the Nile” 2004 news 24.com

17.EPA North East Africa 2010 report

18.Ibid

19.UN Secretary General Kofi Anan

20.Karl Marx. “Capital” A Critique of Political Economy Vol. 1, translated by Samuel Moore and Edward Avelling Ed. F.Engels 1887

21.Paul Collier and Anke Hoeffler. “Economic Causes of Civil War.” Oxford Economic Papers Vol50.4 1998, pp563-573. Also in Paul Collier and Anke Hoeffler Greed and Grievance in Civil War. World Bank Policy Research—Working papers number 2355 May 2000

22.J.R. Stars “Water Wars” Foreign Policy Issue 82 991pp17-20

BBC 12 DEC 2003 also see AL-Ahram, 26 February 2004

23.Ibid also see Ana Elisa Cascao “Ethiopia- Challenges to Egyptian hegemony in the Nile Basin” Water Policy 10 supplement 2 (2008)

24.Ana Elisa Cascao “Ethiopia- Challenges to Egyptian hegemony in the Nile Basin” Water Policy 10 supplement 2 (2008)

25.Ana Elisa Cascao “Ethiopia- Challenges to Egyptian hegemony in the Nile Basin” Water Policy 10 supplement 2 (2008)

26.The Nile Basin Initiative NBI

27.Ibid NBI

28.ibid

29.ibid

30.ibid

31.Gramci 1971 cite in Cascao (2008) p.18

32.World water council report 2009

33.ibid

34.ibid

35.Cascao “water policy” document No. 10

1.Wonddwossen Teshome B. “Transboundary Water cooperation in Africa: The case of the Nile Basin Initiative.” Turkish Journal of International Relations winter Vol. 7.4 2008 pp34-43

Also see Flintan, F. & Tamarat,I Spilling Blood Over Water? The case of Ethiopia, in Scarcity and Surfeit, The Ecology of Africa’s Conflict. Lind &J.& Sturman K.(eds) Institute for Security Studies, Johannesburg (2002)

2.Ibid

3.Ashton, Peter J. “Avoiding Conflicts over Africa’s Resources” Royal Swedish Academy of Science. Vol.31.3, 2002 pp236-242

4.Berman and Paul, “The New Water Politics of the Middle East. Strategic Review, Summer 1999. 21-28

5.Wonddwossen Teshome B. “Transboundary Water cooperation in Africa: The case of the Nile Basin Initiative.” Turkish Journal of International Relations winter 2008 Vol. 7.4 pp34-43

6.Alcamo, J., Hulme, M., Conway, D., & Krol, M. “Future availability of water in Egypt: The interaction of global, regional and basin scale driving forces in the Nile basin”. AMBIO – A Journal of the Human Environment, 25(5), (1996). 336.

7.Oxfam 2009 report

8.Kim, U., & Kaluarachchi, J. J. “Climate change impacts on water resources in the upper Blue Nile river basin, Ethiopia.” Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 45(6), (2009). 1361-1378.

9. ibid

10.World Water Council Report 2006

11.ibid

12.Wonddwossen Teshome B. “Transboundary Water cooperation in Africa: The case of the Nile Basin Initiative.” Turkish Journal of International Relations winter 2008 Vol. 7.4 pp34-43

14.Braune, Eberhard and Youngxin Xu2. “The role of Ground Water in the Sub Saharan Africa.” Vol. 48.2 March 2010, pp229-238

16.Cam McGrath and Sonny Baraj “Water Wars Loom along the Nile” 2004 news 24.com

17.EPA North East Africa 2010 report

18.Ibid

19.UN Secretary General Kofi Anan

20.Karl Marx. “Capital” A Critique of Political Economy Vol. 1, translated by Samuel Moore and Edward Avelling Ed. F.Engels 1887

21.Paul Collier and Anke Hoeffler. “Economic Causes of Civil War.” Oxford Economic Papers Vol50.4 1998, pp563-573. Also in Paul Collier and Anke Hoeffler Greed and Grievance in Civil War. World Bank Policy Research—Working papers number 2355 May 2000

22.J.R. Stars “Water Wars” Foreign Policy Issue 82 991pp17-20

BBC 12 DEC 2003 also see AL-Ahram, 26 February 2004

23.Ibid also see Ana Elisa Cascao “Ethiopia- Challenges to Egyptian hegemony in the Nile Basin” Water Policy 10 supplement 2 (2008)

24.Ana Elisa Cascao “Ethiopia- Challenges to Egyptian hegemony in the Nile Basin” Water Policy 10 supplement 2 (2008)

25.Ana Elisa Cascao “Ethiopia- Challenges to Egyptian hegemony in the Nile Basin” Water Policy 10 supplement 2 (2008)

26.The Nile Basin Initiative NBI

27.Ibid NBI

28.ibid

29.ibid

30.ibid

31.Gramci 1971 cite in Cascao (2008) p.18

32.World water council report 2009

33.ibid

34.ibid

35.Cascao “water policy” document No. 10

Majeed A. Rahman is Professor of African Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Milawaukee.

No comments:

Post a Comment