Deep in Enemy Territory – Fast Times in PalestineBy Pamela Olson |

May 20, 2013

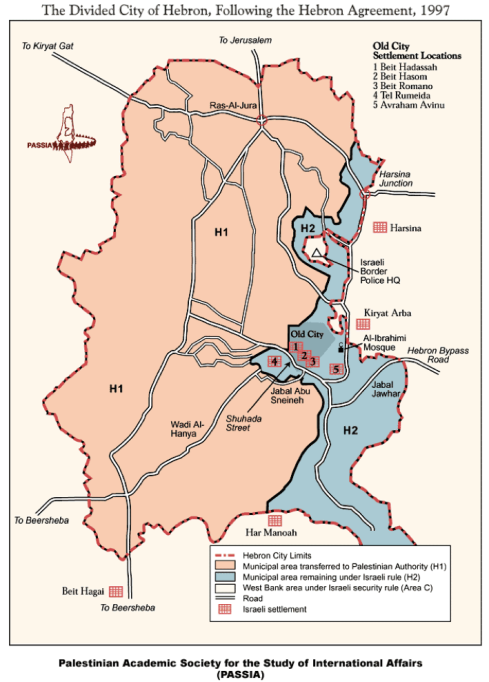

A friend from college named Cameron was in Israel visiting family for Passover. He was an adventurous soul, a world traveler and entrepreneur, with curly brown hair, blue eyes, and a slim athletic build. When his family learned I was in the Holy Land, they invited me to their Passover seder — until they realized I lived in Ramallah, at which point they promptly rescinded the invitation.(The following is an outtake from Pamela Olson’s book Fast Times in Palestine, published by Seal Press in March 2013) Cameron was a strong supporter of Israel and hawkish on security issues, but he was embarrassed by his family’s behavior. I told him he could make it up to me by visiting the West Bank for a week and seeing the occupation for himself. To my pleasant surprise he agreed. In order not to upset his family, he told them he was heading to the Sinai for a week. He arrived in Ramallah just as the Dancing Traffic Cop was beginning his shift in Al Manara. Tall, lanky, and graceful, wearing reflective silver aviator sunglasses, the man didn’t just direct traffic. He made a show of it. Cameron and I watched in amazement as his long arms moved in quick, precise, exaggerated arcs and twirls to match his intricate, impeccable footwork. [See a YouTube video here.] Even when he took a break and headed to the coffee stand under the palm trees, he didn’t just walk. He strutted, smiling with his razor-sharp Robocop jaw line, tipping his hat to passers-by as if he were the uncontested king of Al Manara. Cameron looked at me, demanding an explanation. I could only shrug. I used to wonder, did somebody tell him to direct traffic like that, or was it his own initiative? Had he been a kid like Billy Elliot who wanted to be a dancer but couldn’t because it wasn’t culturally acceptable? If so, why on earth was he dancing in full view of the public, waving and flashing his movie star smile to all who passed by, with apparent unanimous approval? I didn’t question it anymore. I just enjoyed it.  We walked to Pronto to meet John from Kentucky and a handful of other Palestinians and foreigners and chat with them over pizza and beers. I made it a point to take Cameron there so he could see I wasn’t the only crazy person who thought the West Bank could be a lovely place to live. But the next day he would find out just how hellish it could be. * * * Hebron (known as Al Khalil in Arabic) [1], a Palestinian city twenty-five miles south of Jerusalem, is home to the Ibrahimi Mosque, a citadel-like stone structure with two imposing square minarets built over the Cave of the Patriarchs. The Biblical couples Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, and Jacob and Leah are believed to be buried there. Muslims have maintained it for centuries as an important mosque, and for Jews it is the second holiest site in the world after the Western Wall of the Temple Mount. Before the advent of Zionism, Jews lived in relative peace in Hebron. [2] Muslim neighbors lit candles and performed other small labors for Jews during Shabbat. But tensions rose after the Balfour Declaration of 1917, when the British government promised a state in Palestine to Jews who mostly weren’t there yet. The worst attack took place in 1929 when Palestinian mobs descended on Hebron and killed 67 Jews, most of them recent European immigrants. [3] Hundreds of native Jews, most of them Arabic-speaking, were sheltered and saved by their Muslim neighbors. But British officials compounded the assault by ordering Jewish survivors to evacuate the city for their own safety. Hebron was largely devoid of Jews until the spring of 1968, when a rabbi named Moshe Levinger requested the Israeli army’s permission to host a Passover seder in a hotel in Hebron. After the seder he refused to leave. Little by little, with the army’s tacit approval, he and his followers built a settlement called Kiryat Arba near the Ibrahimi Mosque. Kiryat Arba now has a population of over 7,000 and is known as one of the most fanatical settlements in the West Bank. It houses a Memorial Park for Rabbi Meir Kahane, the founder of Kach, a militant Jewish organization designated as a terrorist group by the US and Israel. The grave of Baruch Goldstein, the settler who massacred 29 Muslim worshipers in 1994, is across the street from the park. According to the BBC, "His grave became a pilgrimage site complete with streetlights, a sidewalk and paved area for people to gather, and a cupboard with prayer books and candles. The marble plaque on his grave reads, 'To the holy Baruch Goldstein, who gave his life for the Jewish people, the Torah, and the nation of Israel.’" [4] In 1997, as part of the Oslo Accords, the Israeli government divided Hebron into two parts, H1 and H2. It was touted as a compromise since Palestinians were granted nominal control over H1, which comprises 80% of the city and 120,000 of its residents. But the rest, including the Ibrahimi Mosque, the Old City, Shuhada Street, all the settlements, and 30,000 Palestinian residents, remain under full Israeli control. Shuhada Street has since been declared off-limits to Palestinians, and its hundreds of shops and markets have been shut down.  In 1979, Rabbi Levinger’s wife led a movement of settlers into a handful of sites in and around the Old City, some of which were previously inhabited by Jews (though the settlers themselves have no legal claim to the sites). Five hundred Israeli settlers now live in H2, with 2,000 Israeli soldiers on duty to guard them. The Palestinian population in H2 has been steadily shrinking due to the closures of roads to Palestinians, a ban on Palestinian commercial activities near settlement areas, and settler harassment and violence, which the Israeli army does little to curb. [5] When our service taxi arrived in Hebron, we asked a young woman in a hijab how to get to the Old City. She smirked. "Just walk that way until you see Israeli soldiers." We made our way past the soldiers and into Hebron’s Old City, which was nearly as well-preserved as the Old City of Nablus. But it was eerily empty and quiet. In all of H2, about 40% of Palestinian homes had been abandoned. In the Old City the figure rose to 80%. A few brave souls sat by open shops or carts full of small piles of goods for sale looking like sages or martyrs from another time. They welcomed us warmly, but I had never seen people who looked so worn down by life. Suddenly a stream of filthy water rained down in front of us and narrowly missed Cameron. We looked up and saw a roof of chicken wire over our heads weighed down with garbage. Beyond it was a recently-built structure of smooth sandstone with an Israeli flag fluttering in the breeze. "That’s the settlers," one old shopkeeper informed us. "The settlers throw garbage at you?" I asked, appalled. He chuckled at my naïveté. "Garbage, eggs, rocks, sewage. This is our life."

The wire mesh Palestinians must live under to try to keep out some of the things settlers throw at them

The shops that had lined the street — everything from tourist stores to Turkish baths — had been closed and abandoned, their rusting doors welded shut, their turquoise paint peeling. Strings of plastic Israeli flags fluttered across the empty streets like perverse party favors. Army Jeeps slid by like patrolling sharks. Graffiti was scrawled on the walls in English, Hebrew, and occasionally Russian with messages like "Death to the Arabs," "Arabs are Sand Niggers," "Arabs to the Gas Chambers," and "Sasha Nov 02."  The hairs on the back of my neck stood up. The ethnic cleansing was so brazen, so unapologetic, so recent. Not just recent — it was ongoing. The Palestinians who dared remain in this area had metal grilles on their windows and doors to fend off the rocks and other projectiles hurled at them by settlers. They hurried past checkpoints, their heads bowed, trying as hard as possible to be invisible. Even children on their way to school were sometimes beaten and stoned by settlers. A recent Haaretz article called "Hebron Diaries" had told the story of an Orthodox Jewish soldier named Yehuda Shaul who said he "could not bear the moral erosion he noticed in himself and his comrades" during his year of service in Hebron. "It starts with little things," he said. "At first, you only blindfold real suspects, and in the end you have some teenager who left his house during the curfew sitting next to you blindfolded for 10 hours, and it seems normal to you. A lot of things are done just to demonstrate a presence, to show that the IDF is everywhere at all times. On each patrol, they enter a few houses, put the women and children in one room and the men in another, check documents, turn the house upside down and then leave. There are no terrorists there, no special alerts. It’s just done. And then there’s the shooting, of course. Hours upon hours of shooting from a heavy machine gun or a grenade launcher… Do you know what it means to fire grenades into a crowded neighborhood where people live? And for four hours in a row? It’s a situation that brings out the insanity in people." [6]

Settlers and soldiers make life extremely difficult for Palestinians in Hebron. At least one school has been forced to close because students were harassed so badly by Israeli settlers

Back in the light of day we headed to H1 to see what H2 must have looked like before the settlers came. I called a man named Hisham who had applied to work at the Palestine Monitor and asked if we could meet him for coffee. He agreed and then showed us all around the streets of H1, which were colorful and bustling, in shocking contrast to the post-Apocalyptic vibe in H2. He directed us to his friend’s appliance store, which had a secret lounge upstairs plastered with images of Che Guevara. He poured us each a glass of wine (which we had to drink behind closed doors in this conservative city), and his friend prepared a huge dinner of kofta bandoora (spicy minced lamb baked with potatoes and tomatoes) with bread and yogurt. They told us over dinner that Hebron was known in the Arab world for its poetry and artistic glasswork and for being the butt of Palestinian jokes. Hebronites (Khalilis in Arabic) are known as the hillbillies of Palestine in part because of their accent, which has a sing-song quality. I explained what an 'Okie’ was and told him we apparently had something in common. We spent the rest of the evening drinking wine, smoking nargila, and telling Khalili jokes. * * * The next day Cameron and I took a service taxi to the Dheisha Refugee Camp near Bethlehem. We entered the camp and I found a receptionist at the Ibdaa Cultural Center and asked if there was anyone who could show us around the camp. "Probably you should talk to Jihad," she said. Cameron tensed beside me, unable to parse the strange sentence. He didn’t know 'Jihad’ was a common name in the Arab world. Jihad arrived a few minutes later. He had a medium build, a light beard, and the sporty wardrobe and tightly-coiled defensiveness of a ghetto youth. He greeted us politely without meeting our eyes and took us on a quick walking tour. It was standard fare for a Palestinian refugee camp — narrow streets, concrete buildings, cramped alleys, and occasional touches of bougainvillea or decorative tiles to lend a whiff of dignity. The residents were mostly from villages west of Bethlehem that had been depopulated and destroyed in 1948. The ruins of their villages were just a few miles away. Their hilly lands had been forested with conifers and turned into an Israeli national park. Jihad took us back to the Ibdaa Center and showed us a game room where two middle-aged men in tank tops were playing a fierce game of ping pong. When one missed a tough shot he muttered under his breath, "Allahu akbar!" Cameron looked at me, alarmed. This was another word like jihad that only meant political hate speech in Cameron’s mind. I whispered, "They say Allahu akbar in a lot of different ways. Sometimes ironically. Right now he’s saying it like, 'Good Lord!’ or 'God Almighty!’" "Ah." Cameron relaxed. He even seemed to smile a little, as if the world had suddenly become slightly less dark. As Jihad got to know us better, his bored affect began to melt away. He told us a performance would take place that night in the center’s small theater and invited us to attend. The performers were a group of disarmingly self-possessed children from the camp who sang and danced with the names of their destroyed villages hanging around their necks. They all held keys in their hands, symbols of the homes their parents and grandparents had left behind. The implication was unmistakable: Sooner or later, one way or another, they would reclaim their birthright and return home. Cameron looked deeply shaken. * * * The second round of local elections was scheduled to take place the next day, May 5. When Cameron and I arrived in Jayyous we could feel the excitement in the air, a sense of joy and disbelief that people had some agency in their lives for once. I didn’t ask about people’s political affiliations, but they began falling into slots in my mind. Two of Rania’s brothers were Fatah policemen, and I could only assume they’d be voting for their own paychecks. Qais’s family was harder to place. They seemed apolitical, just trying to study and work and live. Amjad’s TV was usually playing Al Manar, Hezbollah’s satellite channel. This, along with his obvious hatred for Fatah, meant he probably supported Hamas. Hamas had an armed wing called the Izzedine al Qassam Brigades, but "Approximately 90 percent of its work is in social, welfare, cultural, and educational activities," according to Israeli scholar Reuven Paz. [7] Such works include schools, orphanages, healthcare clinics, soup kitchens, and sports leagues. I was beginning to realize by now that it was possible to support Hamas without supporting attacks on Israelis the same way it was possible to vote Republican without supporting the Iraq War. Like Americans, Palestinians put a high priority on domestic considerations. For many Palestinians, a vote for Hamas meant voting for the less corrupt party, the 'values’ party, the party that provided certain public services, or simply the only viable alternative to Fatah. All day we saw kids in green headbands running down the streets shouting, "Intikhabat! Intikhabat!" (Elections! Elections!) or "Hamas! Hamas!" Cameron laughed. "If I’d seen these kids wearing green headbands and yelling for Hamas on the news, I would have been horrified, like they were all little terrorists-in-training." "And now?" He shrugged. They were obviously just kids, excited by the hope in the air that things might actually change, even just a little bit. We both wished we’d ever seen anyone, young or old, look this excited about elections in America. Voter turnout was high in Jayyous, and Hamas won in a landslide. * * * Nablus was our final stop. We made it through the Huwara checkpoint without problems, and Nick met us in Nablus’s main traffic circle. He looked restless and excited as he led us to the Balata Refugee Camp, where he said a militant rally was taking place. Cameron looked anxious but gamely followed. The crowd thickened as we neared a small stadium packed with onlookers. Nick muttered, "The rally’s being put on by the Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades. The PA is just starting to assert control over 'lawless’ areas. Balata Camp is one of them, and it’s an Al Aqsa stronghold." "Aren’t the Al Aqsa Brigades part of Fatah?" I asked. "Yeah, they’re an armed offshoot of Fatah. But they have cells all over the West Bank, and the cells usually have some level of autonomy. Right now Palestinian police can’t even go into the Old City. They don’t dare. It’s the militants’ stomping grounds." His eyes widened and his voice dropped further. "The police are coming in now. You see them?" "Yeah," I whispered back. "What are they doing?" "I think they’re just here to assert their presence." We could see them and the militants eyeing each other with the tension of estranged brothers in the same room. I began to feel nervous. The first big clash between the Al Aqsa Brigades and the PA police might be brewing right here. A militant started giving a speech. At one point he stopped, stared at the policemen, and fired a single shot in the air. The policemen didn’t react other than clutching their guns more tightly. We quietly slipped out, and the rally ended later without incident. But it was another harbinger of changing times. Over the next few years, nearly all the militants in Nablus would be finished off, bought off, disbanded, or absorbed into the police. They still ruled the city now, though, and as we walked through the Old City, a group of young militants surrounded us and started chatting with us. They didn’t seem threatening, just bored. One of them, a goofy, awkward youth, had a baby face and was missing an arm. His gun was slung over his stump, and he was constantly adjusting it as he shuffled down the alley. Cameron ducked and shifted every time the gun momentarily came to rest pointing at him. It was like looking at ghosts in a way. They had essentially called a death sentence upon themselves by picking up guns in this environment. This young man would be killed by Israeli soldiers in the next few months. Nick would see his face on a poster. We walked to the Yasmina Hotel. An Egyptian film from the sixties was playing in the lobby. Cameron did a double-take when he saw it. The women wore skimpy clothes and the main character, played by Egyptian actor Adel Imam, looked and acted like Cheech Marin. "Things were a lot more liberal and laid-back in the sixties and seventies," I explained. "The religious revival didn’t really start until after Israel defeated the secular Arab nationalists in 1967." When we got to our room, Nick asked Cameron what had struck him most during his stay in the West Bank. "Those kids with the names of their villages around their necks in the Dheisha Refugee Camp," he said. "Israel will never let the refugees return. It would mean the end of Israel as a Jewish-majority democracy. But the way those kids are being brought up, I don’t see how they can be happy without it. With that kind of thinking, I don’t see how there can ever be peace." He shook his head bleakly. "It’s a lot more hopeless than I thought." In later years I would reflect on the irony of the fact that he was criticizing the refugees for their inflexibility in demanding their rights when he was just as rigid in his unquestioned belief that their rights must necessarily be denied. . To learn more about Fast Times in Palestine, visit the book’s website orAmazon page.

NOTES 1. The Arabic name for Hebron, Al Khalil, derives from Ibrahim al Khalil al Rahman, or 'Abraham the Friend of God.’ Al Khalil means 'the friend’ whileAl Rahman means 'the merciful,’ one of the many Muslim names for God. Here it refers to God’s mercy in staying Abraham’s hand and not forcing him to sacrifice his son. 2. Lital Levy, "A descendant of the city’s 500-year-old Jewish community starts a movement to restore a tradition of coexistence between Muslims and Jews," Christian Science Monitor, May 20, 1997. 3. According to Noam Chomsky’s book Fateful Triangle: The United States, Israel, and the Palestinians (South End Press, 1999), "The massacre followed a demonstration organized at the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem to counter 'Arab arrogance’ — 'a major provocation even in the eyes of Jewish public opinion’ (Flapan, Zionism and the Palestinians, p. 96). See Sheean, in Khalidi, From Haven to Conquest, for a detailed eyewitness account. This provocation was organized by Betar, the youth movement of Vladimir Jabotinsky’s Revisionist organization, which is the precursor of Begin’s Herut, the central element in the Likud coalition." 4. "Graveside party celebrates Hebron massacre," BBC, March 21, 2000. 5. "Police, soldiers and military officers prefer to 'turn a blind eye’ instead of handling incidents in which settlers attack Palestinians in the West Bank." See: Uri Blau, "Behind closed doors, police admit 'turning a blind eye’ to settler violence," Haaretz, August 15, 2008. 6. Aviv Lavie, "Hebron diaries," Haaretz, June 18, 2004. 7. "Backgrounder: Hamas," Council on Foreign Relations, August 27, 2009. . . . Source |

Friday, 24 May 2013

Deep in Enemy Territory – Fast Times in Palestine

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment