Another thousand acres

Binyamin Netanyahu orders the biggest land-grab in a generation

SOME people are never grateful. On August 31st Israel’s But it was not enough for the area’s Israeli mayor, Davidi Perl. Frustrated by what he perceives as the government’s grovelling to westerners, on everything from the recently halted war in Gaza to the conduct of peace talks with Palestinians, he says he will change party—defecting from Likud, led by the prime minister, Binyamin Netanyahu, to Jewish Home, a party of religious radicals headed by Naftali Bennett.

Many others are following. A poll on September 2nd showed that Mr Bennett had, in effect, replaced Mr Netanyahu as champion of the right-wing camp. Although Mr Netanyahu’s approval ratings are roughly on a level with where they stood before the 50-day war in Gaza, much of the approval comes from Israelis who vote for parties left of Likud. Challengers within his party are demanding more aggression in Gaza, where the ceasefire left no clear winners, and faster entrenchment of settlements in the West Bank, even though the settler population is growing three times faster than that of Israel proper.

During the Gaza war former loyalists like Gidon Saar, his interior minister, repeatedly denounced the ceasefire deal, which envisages a gradual easing of the blockade on Gaza. A bruised Mr Netanyahu is resorting to political outreach. He and his wife, Sara, are hosting party members in the run-up to the Jewish new year. After months of relying on statements, he is again giving televised interviews.

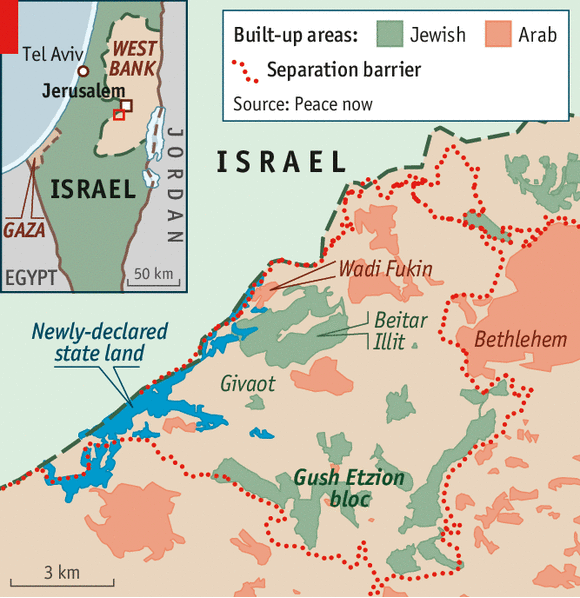

Mr Netanyahu’s supporters hope that settlement expansion will shore up his core backing on the right. Four parliamentarians come from Gush Etzion, including the foreign minister, Avigdor Lieberman, the Knesset speaker and the head of its powerful foreign affairs and defence committee. The new settlement, they hope, will assuage the anger at the killing of three Jewish students, whose capture outside a religious school in Gush Etzion sparked the Gaza war.

But the more Mr Netanyahu indulges the right, the more he alienates the outside world. America, the UN and the European Union have urged Mr Netanyahu to reverse course. The British prime minister, David Cameron, denounced the expansion as “utterly deplorable”.

To its foreign critics, Mr Netanyahu’s government tries to minimise the move. Tendering for construction has yet to begin, officials note; and even if it should, the land abuts the green line and lies inside blocs of territory that Israel would anyway annex under any conceivable peace agreement with Palestinians.

Nevertheless, hopes of reviving peace talks are evaporating, just as they did when Mr Netanyahu’s last land appropriation in March made peace talks go “poof”, in the words of John Kerry, the American secretary of state. Mr Netanyahu may have negotiated the Gaza ceasefire with a Palestinian delegation that included the Islamist Hamas movement, which rules Gaza. But he says he will not talk peace with the Palestinian president, Mahmoud Abbas, as long as his government is backed by Hamas. His defence minister, Moshe Yaalon, says the arms build-up in Gaza shows that Israel cannot cede the West Bank.

Spurned again, and under pressure from a resurgent Hamas, Mr Abbas is toying with asking the UN to impose a three-year deadline for ending Israel’s occupation of the West Bank. Even some settlers, along with Mr Netanyahu’s centrist rivals, wonder whether the prime minister has gone too far. “It’s stupid to accelerate Israel’s delegitimisation with steps which make Israel look radical and Palestinians level-headed,” says Yair Kahn, a rabbi at Har Etzion, a large yeshiva in Gush Etzion with a reputation for pragmatism.

Encircled by Mr Netanyahu’s latest appropriation, Palestinian residents of the bucolic village of Wadi Fukin have already lost all but 450 of the 3,000 acres they once had, and stand to lose more. The hillsides where the village’s 600 sheep and goats graze are set to go. Unable to farm, many men find work as builders, often on Jewish settlements nearby. They may yet be called upon to build homes for Israelis on land they regard as their own.

No comments:

Post a Comment